MACCSI

In 1972, the major construction project of Caracas’ Central Park had begun and the President of the CSB, Gustavo Rodriguez Amengual, expressed his special interest regarding the development of arts in culture within the large-scale urban redevelopment plan and his hope for the integration of an “Exhibitions Hall” to serve as an vehicle for the bourgeoning national creativity that would contribute to the enrichment of culture in the capital city. At this moment is when the government solicited the acquisition of a prominent collection of European avant-garde artists to permanently place in this newly conceptualized Exhibitions hall.

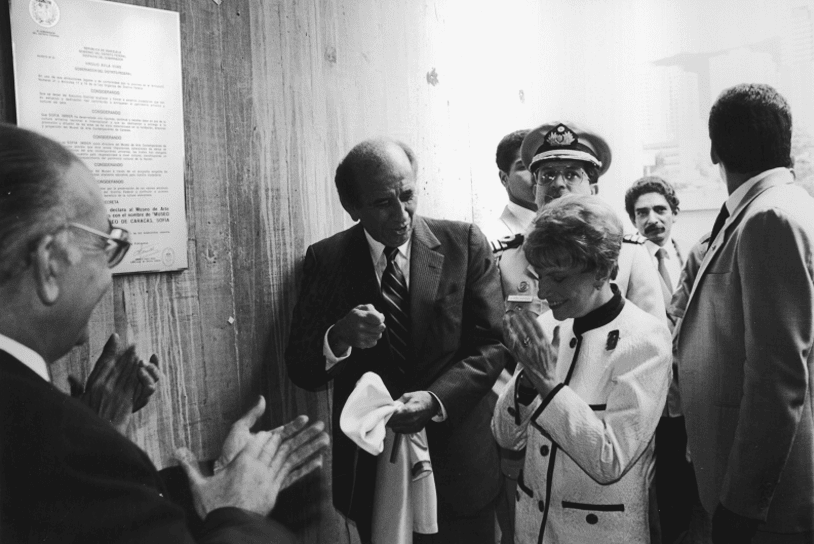

Working with many critics, Sofia took it upon herself to extend the reach of the proposed collection to create what would one day be called the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas Sofía Imber (MACCSI), and, together with Alfred Boulton, planted the idea to transcend the plan of a mere exhibitions hall and to place instead a functioning museum of contemporary art that would provide the citizens of Caracas and Venezuela with an institution with the proper transformative power to create the dynamic cultural destiny that they merited and deserved.

In Caracas at that time, there was no contemporary art museum and Sofia assumed the challenge of creating one. The redevelopment agency oversaw the urban revitalization project and gave Sofia a small parcel of land for her proposed institution, and she responded with “It doesn’t matter, they could give me a garage and I will convert it into a museum.”

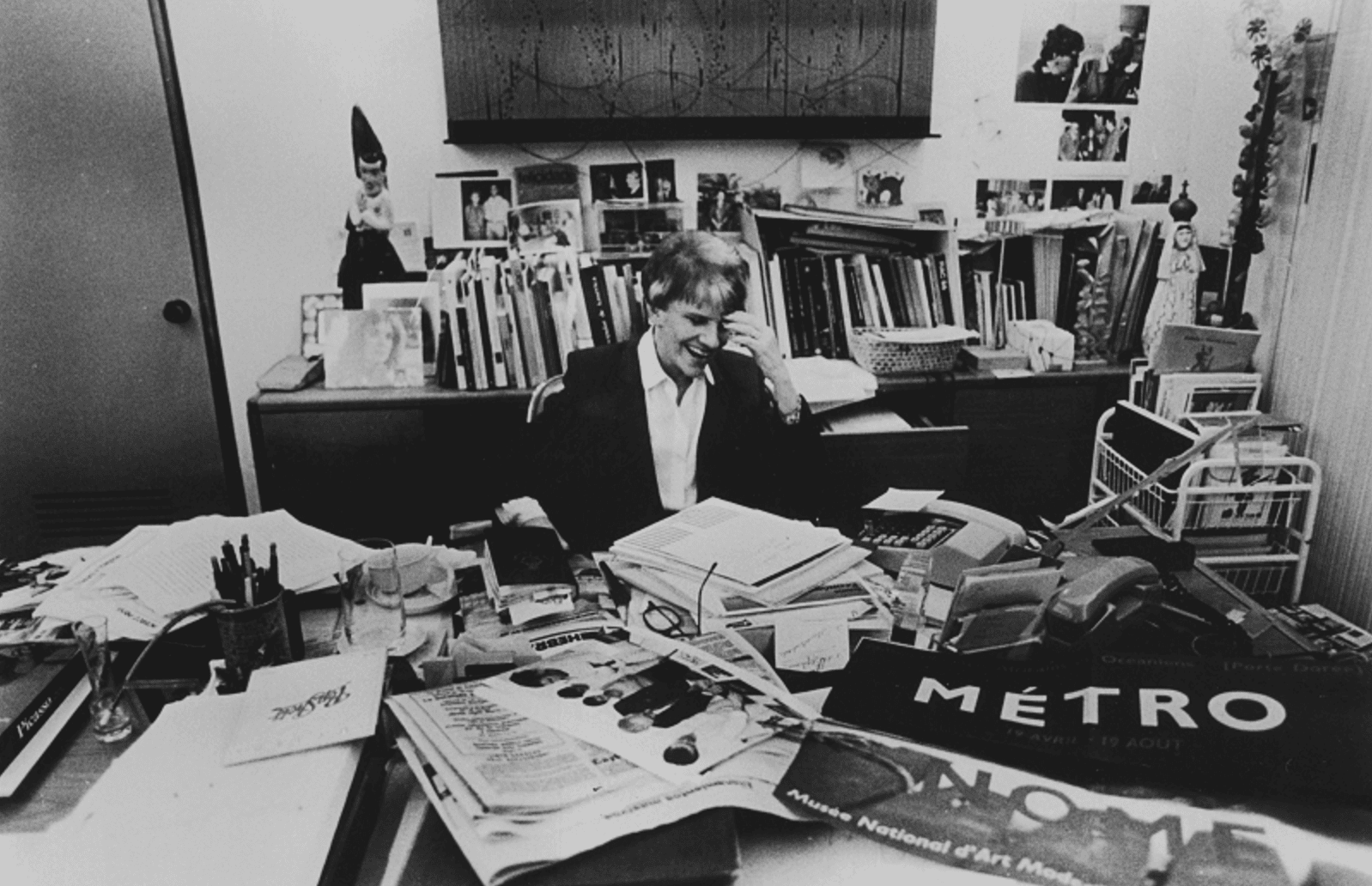

With time, not only was a garage given to her, but also parking spaces, useless awkward lots and impossible corners that Sofia diligently incorporated into the culmination of the institution that quickly grew from having 3 exhibitions galleries to a total of 16 fully climatized galleries, an employee dining hall, carpentry workshops, restoration studios, the first public library with a focus on art and art history, special galleries specifically for the blind, conference and concert halls, a Museum Café, a sculpture garden, and the legendary administrative offices of the MACCSI.

Her primary objective was to improve the lives of the residents of Caracas and Venezuela through interactions with the leading art and artists of the period with the thoughtful education of those from the community who had traditionally been marginalized or overlooked. The museum was a pioneer in this realm for Venezuela. One of the major accomplishments of this initiative was the MACCSIBUS which would travel the entire country with exhibitions, a library, videos, and educational courses bringing art and culture not just to the capital city but to some of the most remote areas of the country.

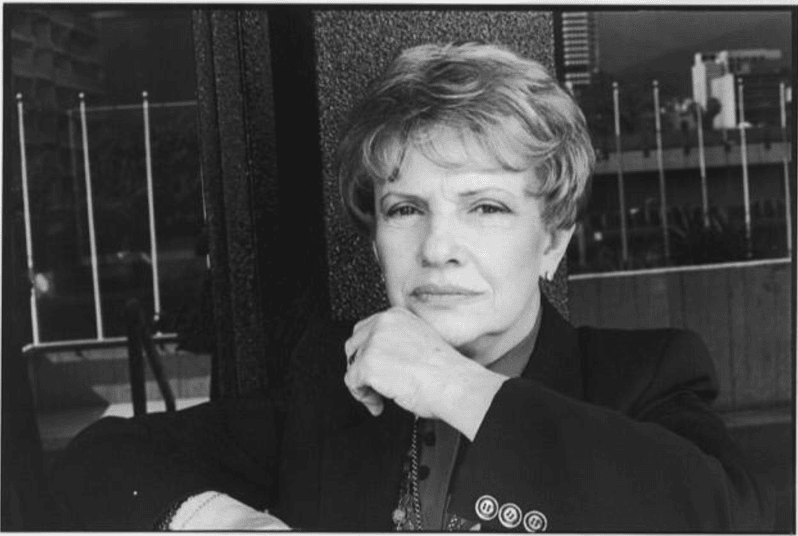

It seemed easy, and in reality, Sofia’s success was guaranteed and any challenge she would have taken on she would have accomplished by the mere fact of her character and drive. But Sofia was not content with her first steps and proposed to elevate the newly created museum to the same level of national museums across the globe. She honed in on her message and set out to use culture in a way that had never been seen before in Venezuela. The museum was converted into the paradigm of what we know today as an “open museum,” a precursor to the many of the social programs in Venezuela, binding together the institution with the community it set out to serve. With this change, she also shifted the perception of culture with the government of the country. Sofia created the standard and expectation for public financial support of the arts; she knew how to accomplish this and committed herself fully to justifying the needs for public funds in support of arts and culture, forevermore changing the dialogue in Venezuela.

The collection of the museum was also another fantasy or dream which was made into reality by Sofia. In those times, nobody imagined what Sofia had in store for the walls she helped build, not even her own staff working at the museum.

In 1981, the museum received Dora Maar by Picasso and The Odalisque by Matisse – which were followed in succession by Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, and Joan Miró which were added to the foundation of the collection she had already worked hard to bring together, while also representing masterworks by Francis Bacon, Fernando Botero, Victor Vasarely, and Lucio Fontana. In a matter of two to three years from its founding, the museum could count a significant collection of Picasso’s on its walls. Nobody could believe it. In her mind, Sofia wanted the collection and each piece in it to function like a constellation in the night sky, where each work shines on its own but its brilliance is only multiplied when placed alongside the others. This allows for an infinite number of intersections that deeply enrich the way in which themes can be explored and presented to the public at large.

This is one of Sofia’s greatest talents. Being able to select the work of art that best represents the artist and choose the piece of greatest quality. This is why for many artists it was an honor to have a piece selected by her, and in fact, many of the major works in the collection were given as gifts by the artists themselves, counting among these the celebrated “Cat” together with 17 other sculptures from Botero entered the museum’s collection. There is no other collection in the world that so clearly reflects the soul of its curator the way this collection reflects Sofia, with every beat of its heart. There are other collections that better reflect each of the movements of the 20th century, or with a larger number of works…but the collection of the MACCSI jumps ahead of academic criteria and goes directly to the essence, the soul of the work. Sofia Imber has an “eye” like no other, she knows art, has lived it, has felt it, and has participated in the very movements that defined the 20th century.

The exhibitions she organized are also legendary and form a rich heritage for all art history, artists, and the general public in Venezuela.

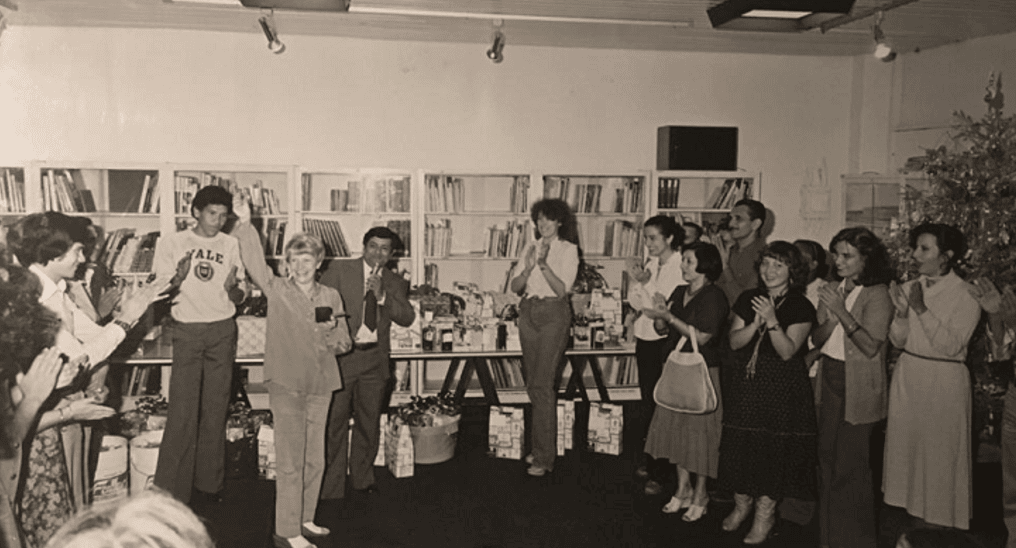

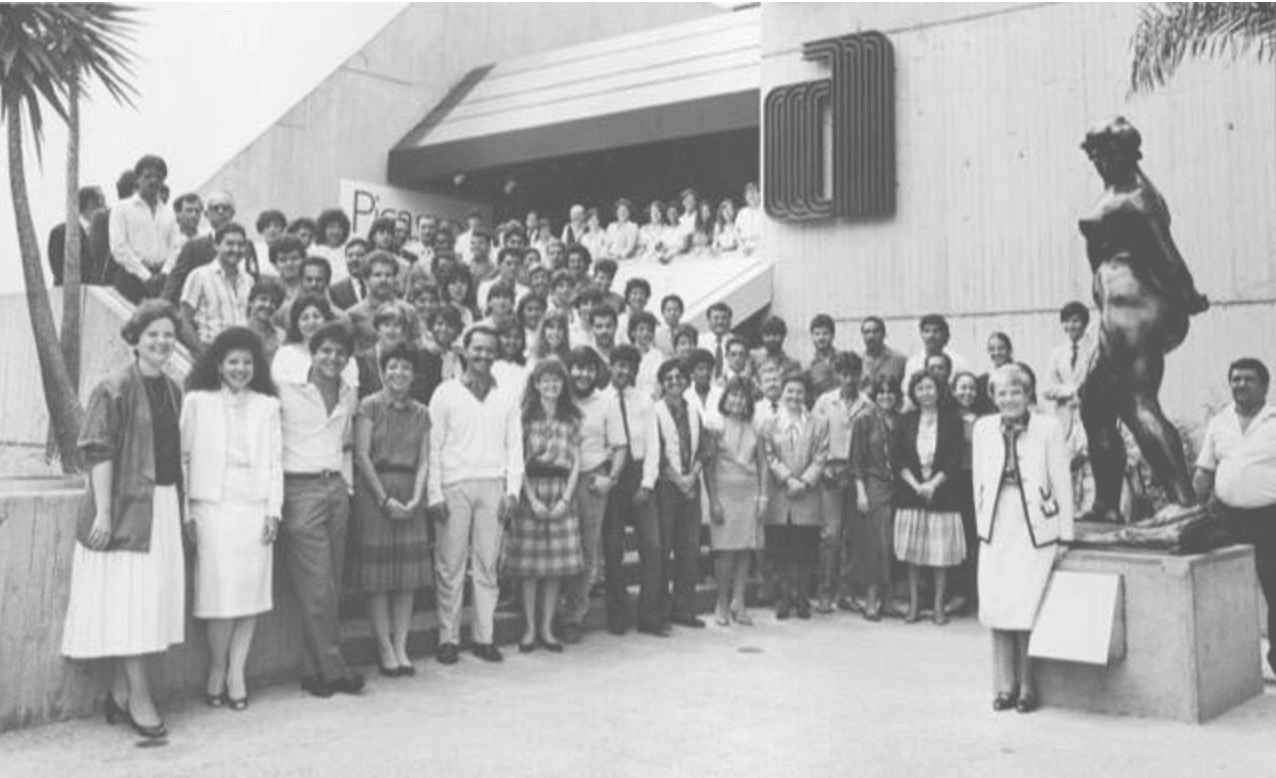

Apart from her personal talents, the museum was also a model of existence – it was not simply a “job” for those who worked there. Working at the museum under Sofia’s direction transformed the lives of employees to embrace a life of service through the medium of the arts. At the museum, employees grew not only as professionals but as people. Under the spirit of an institution striving for excellence and with an unprecedented collection in the country, the employees of the museum developed their sense of nationalism and pride of their country and its contributions. Their work was not marked by tasks but by the experience defined by the vision and soul of Sofia Imber.

MACCSI was also a home and a family. In an essay by intellectual Julio Ortega describes with accuracy this experience “MACSSI,” he writes “plays the role of home: one easily recognizes its rituals of hospitality. It was built not only for the representation of artistic treasures but to welcome and cherish them at each and every one of our visits. It is not a temple for ceremonies but a threshold into a greater world. Because of this, we maintain intimate personal relationships with each of its monuments.

All of this, together with her absolutely rare, admirable, tireless, and radical capacity for work, her dignity and strength, her example as a human being and her love of Venezuela, are the invaluable lessons that our country had received from Sofia.”